Executive Summary

Gray’s Reef National Marine Sanctuary, located off the coast of Georgia, was designated in 1981 to protect one of the largest known nearshore “live-bottom” reefs of the southeastern United States. The sanctuary encompasses approximately 22 square miles and is situated roughly 19 miles east-southeast of Sapelo Island, Georgia on the eastern continental shelf of the United States.

This condition report uses the best available information to assess the status and trends of the sanctuary’s resources and ecosystem services from 2008 to 2022. The report is structured around a Drivers-Pressures-State-Ecosystem Services-Response model (see the earlier section, DPSER Framework, and Figure FCR.1 for more information on the model). It assesses water quality, habitat, and living resources, as well as the human activities that affect them, and also includes the first evaluation of the status and trends of the sanctuary’s ecosystem services—the benefits that humans derive from different ecosystem attributes for their lives, lifestyles, and livelihoods.

Status and Trends of Drivers and Pressures

The primary pressures on GRNMS water quality, habitat, and living resources were visitation and use; coastal development and nearshore construction; nonpoint source pollution; changing ocean conditions (including ocean warming and acidification); and non-indigenous species. The primary focus of sanctuary management is on activities that can be controlled at the site, such as non-indigenous species and visitation and use. Other pressures act at regional or global scales, and are thus not the focus of local management efforts; however, their impacts on sanctuary resources are addressed in the Status and Trends of Sanctuary Resources section of the report.

Human Activities

The primary human use of GRNMS is recreational fishing, which is an important way that visitors experience and connect with the sanctuary. Recreational fishing and associated vessel use can impact sanctuary water quality, habitat, and living resources through waste disposal and pollution, introduction of marine debris, illegal anchoring, wildlife strikes, noise disturbance, and harvest. Some metrics suggested vessel and recreational angler activity have increased at GRNMS, but most available data sets were regional and not specific to the sanctuary. Passive acoustic monitoring showed that vessel use in the sanctuary elevated ambient noise levels during the study period. Additionally, lost fishing gear was the most common type of marine debris observed in sanctuary habitats; however, no data were available to understand how the introduction of marine debris may have changed over time. Enforcement records showed that illegal fishing and anchoring occurred during the study period, but enforcement patrols and the detection of these violations were both few in number.

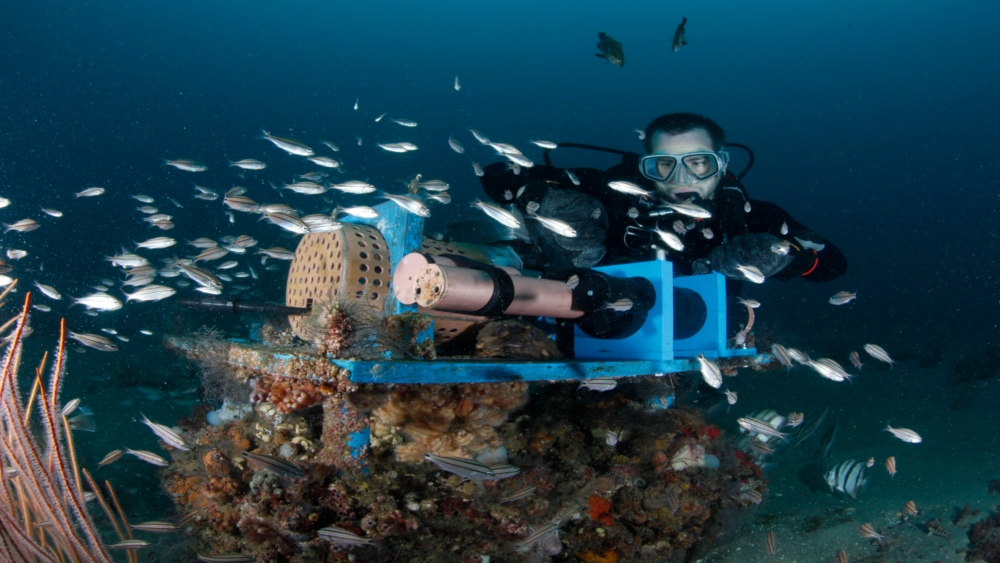

Other common uses of the sanctuary are recreational scuba diving and scientific research. One recreational dive charter is known to visit GRNMS, and the number of private and charter recreational divers at the sanctuary is relatively low due to the site’s distance from shore and challenging oceanographic conditions. The majority of scuba diving at GRNMS is for scientific research. Both recreational and scientific diving are believed to have minimal impacts on sanctuary habitats. Broader research activities, such as sample collection and installation of monitoring equipment, can impact habitats and living resources, but GRNMS permitting controls helped ensure no major disturbances occurred during the assessment period. Marine research often requires the sustained presence of large research vessels within the sanctuary. While this increases the risk of impacts to the sanctuary from spills, no significant spills or discharges occurred within the sanctuary from this or other vessel activity during the study period.

Coastal development can negatively impact water quality via increased runoff and associated introduction of contaminants, and can also negatively impact nearshore nursery habitats for species that use the sanctuary as adults. During the study period, areal cover of saltwater marsh habitat in coastal Georgia remained stable, while areal cover of impervious surfaces grew slightly.

Status and Trends of Sanctuary Resources

In addition to evaluating human activities, the condition report rates the status and trends of water quality, habitat, living resources, and ecosystem services in GRNMS based on data indicators for each focal area. Criteria for indicator selection included: long-term data availability, importance to the ecosystem and culture, responsiveness to changes in environmental conditions, measurability, relevance to standardized sanctuary condition report questions, and responsiveness to management actions. The section below summarizes the most noteworthy results.

Water Quality

No evidence of eutrophication was observed at GRNMS. Indicators of eutrophication, including chlorophyll concentrations and anomalies, dissolved oxygen, and turbidity, generally exhibited consistent and expected seasonal patterns. Sanctuary-specific data on human health indicators were limited; available data, including regional data, suggest sanctuary waters pose few risks to human health. Recommendations to limit consumption of king mackerel and black sea bass, two commonly fished species at the sanctuary, were issued during the study period due to elevated levels of mercury and arsenic, respectively. Although there was little evidence to suggest human health impacts, increased monitoring of human health indicators within sanctuary boundaries is needed to fully inform this question.

Although changing ocean conditions did not result in measurable resource impacts at GRNMS during the study period, changes in a number of parameters occurred on a regional scale. Sea surface temperature increased, marine heatwaves became more frequent, and the number of annual storms increased. Additionally, atmospheric CO2 increased, resulting in greater transfer of CO2 into sanctuary waters, which makes water more acidic, threatening marine organisms.

Contaminant discharges from vessels were another concern for GRNMS water quality. Although some spills occurred regionally during the study period, none were reported within sanctuary boundaries, nor was any spilled material observed in the sanctuary. However, the impact of regional events on sanctuary waters remains unknown due to a lack of sampling for contaminants in the water column.

Habitat

Although GRNMS is known for its live-bottom reefs, most of the seafloor within the sanctuary’s boundaries is composed of unconsolidated soft sediment, which provides habitat for a wide variety of infaunal invertebrates. Changes to habitats in the sanctuary, including physical attributes of live-bottom ledge structures, which are associated with species richness, diversity, and abundance, are largely believed to be driven by natural processes. However, there is a need to analyze and compare more recent benthic profile data to understand whether any substantial changes in habitat distribution occurred; this constitutes an analysis gap for this report. Cover of habitat-forming sessile benthic invertebrates, including sponges, tunicates, and the coral Oculina arbuscula, was stable. Anthropogenic noise was detected in acoustic studies of the sanctuary, but was relatively low compared to some other national marine sanctuaries, and was largely attributed to short-duration vessel transits through the sanctuary.

Data on contaminants in sanctuary habitats were limited, but available studies indicated most contaminants were undetectable or below thresholds for concern in GRNMS sediments. However, microplastics were found in all sediment samples collected in 2021, and are an emerging concern. Some samples of biota from the sanctuary had elevated levels of contaminants, including cadmium and arsenic, suggesting the presence of contaminants in the local environment. Testing of sediment and biota samples for a full suite of contaminants last occurred in 2012–2013; newer data are needed to fully assess the status and trends of contaminants in the sanctuary.

Living Resources

Focal species are those important for economic, cultural, spiritual, recreational, ecological, or conservation-related reasons, as well as those that may be subject to special state or federal protections. Some GRNMS focal species reside in the sanctuary year-round (red snapper, tomtate, black sea bass, king mackerel, the coral Oculina arbuscula, and Halymenia spp. algae), while others are wide-ranging species known to transit through the sanctuary (loggerhead sea turtles, North Atlantic right whales, and sand tiger sharks). Given the diversity of indicator species assessed, the status and trends of focal species were mixed. Resident fish species and Oculina arbuscula remained stable or improved within the sanctuary (however, sanctuary-specific trends may not match regional trends for these species). Conversely, North Atlantic right whales remained endangered and experienced an unusual mortality event during the study period. Data gaps precluded a complete understanding of the status and trends of loggerhead sea turtles, sand tiger sharks, and Halymenia spp. within the sanctuary.

The abundances of non-indigenous species, including lionfish, titan acorn barnacle, and orange cup coral, were low. However, species typically found in tropical waters have been newly observed or are becoming more abundant in GRNMS, likely as a result of increases in seawater temperatures in the sanctuary. These species include lane snapper, red grouper, yellowtail snapper, the branching vase sponge Callyspongia aculeata, and the macroalgae Platoma gelatinosum. More systematic and frequent monitoring is needed to fully understand any impacts of these potential range shifts on GRNMS biodiversity. Available data suggest fish and benthic community structure has remained stable. However, most biodiversity data have been collected in the summer season; year-round monitoring is needed to better understand how biodiversity metrics may change seasonally.

Status and Trends of Ecosystem Services

Ecosystem services evaluated in the report included science, education, heritage, sense of place, consumptive recreation, and non-consumptive recreation.

GRNMS is valued as a longstanding scientific research site in the South Atlantic region. Most indicators of scientific research activity, including the number of permits issued, publications, and active projects, were stable. However, the availability of vessel platforms for conducting research was limited during the study period, and was insufficient to meet GRNMS science goals. Similarly, educational programming was hindered by staffing shortages during the study period. However, programming and exhibits by partner institutions, as well as virtual engagement through the GRNMS webpage, social media accounts, and interactive touchscreen kiosks, provided key opportunities to learn about the sanctuary. In 2022, the Gray’s Reef Ocean Discovery Center was dedicated; though this occurred at the end of the study period, it represents a significant improvement in the ability of GRNMS to provide education and outreach.

Increasing recognition and awareness of past and modern human connections to GRNMS have helped to define its heritage. Artifacts recovered from the sanctuary provide evidence of human habitation of the area now designated as GRNMS when it was fully terrestrial (approximately 3,000 to 13,000 years before present). Information on more recent heritage ties between Indigenous Peoples and the sanctuary remains a data gap. Within the past century, the heritage of GRNMS has largely been shaped by its marine research legacy; Milton “Sam” Gray, the sanctuary’s namesake, conducting trailblazing studies of the sanctuary’s unique ecology. These studies and many since have helped to expand recognition of the sanctuary’s value for scientific research, ultimately supporting the establishment of the sanctuary’s designated Research Area in 2011. GRNMS and the surrounding region also have strong heritage connections to fishing, which has remained important across generations. Fishing has also historically been an important component of Gullah/Geechee culture. The experiences of Gullah/Geechee and other fishers in coastal Georgia waters and GRNMS have been documented in oral histories.

Creating a sense of place for GRNMS has been challenged by a lack of awareness about the sanctuary among most people, although indications of improvement were documented during the study period. Increased public awareness of the sanctuary has been promoted through news, journal, and magazine articles; research publications; television programs; video documentaries; educational exhibits; social media; and special outreach events. GRNMS is known among anglers as a valued sport fishing and recreational diving destination, and its sense of place is strengthened by the presence of iconic species valued for fishing and wildlife viewing, including red snapper, king mackerel, black sea bass, loggerhead turtles, and North Atlantic right whales. More information is needed to fully assess this ecosystem service, including dedicated studies of sense of place, and particularly information on sense of place among the Gullah/Geechee people as it relates to GRNMS.

Consumptive recreation, specifically recreational fishing, is an important ecosystem service provided by the sanctuary. Regional and sanctuary-specific data suggested that this service remained stable during the study period. Because of its distance from shore, recreational fishers visit GRNMS less frequently than inshore sites. Those who do visit the sanctuary had mixed opinions about the status of pelagic fish populations, with approximately equal proportions reporting they perceived these resources were improving, not changing, or getting worse.

Non-consumptive recreational activities at GRNMS include scuba diving and boating, however these activities are also somewhat limited by the sanctuary’s distance from shore, as well as ocean conditions and weather. Although the number of divers known to visit the sanctuary may be limited, those who do visit value it, as evidenced by numerous repeat dive charter customers. Awareness of the uniqueness of GRNMS as a diving destination has also increased over time.

Response to Pressures

During the study period, GRNMS responded to pressures through regulatory measures, education and outreach, and other initiatives. One of the most significant regulatory changes during the study period was the designation of a dedicated Research Area in the southern third of the sanctuary. Fishing, diving, transporting unsecured fishing gear, and stopping a vessel are prohibited within the Research Area. Additionally, GRNMS maintained sanctuary-wide prohibitions on activities that may harm the sanctuary, including anchoring of vessels and harvest of marine organisms by methods other than rod and reel.

GRNMS has also worked to inform the public about the sanctuary’s unique ecology and regulations in place to protect it. Education and outreach efforts have included virtual reality dive tours of GRNMS; web and social media content; magazine articles; interpretive signage at boat ramps and marinas; and collaborative sanctuary exhibits at partner institutions. The GRNMS Sanctuary Advisory Council includes representatives from a wide variety of user and other interest groups, including the sport fishing and recreational diving communities, two of the biggest sanctuary user groups. GRNMS has developed specific outreach materials for fishers and divers to share information and best practices for responsible use of the sanctuary.

Scientific research activities during the study period have helped to inform management action. For example, studies of vessel activity at GRNMS have aided in understanding patterns of use. Sanctuary managers rely upon data streams from National Data Buoy Center station 41008 (located within the sanctuary), which provides real-time weather and safety information to sanctuary users, but also generates key oceanographic data to aid GRNMS in monitoring and understanding changing ocean conditions. Scientific partnerships with government, academic, and nonprofit organizations have helped to leverage these data and generate new information about sanctuary biology, ecology, chemistry, paleolandscapes, and more. The potential impacts of scientific research itself continue to be managed through careful permitting and review of after-action reports.

Although GRNMS does not have management authority over coastal and offshore development, it works with various partners and the Sanctuary Advisory Council concerning activities that may affect the sanctuary. For example, the advisory council sent a letter to the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management in 2015 opposing a proposed draft oil and gas leasing program for the continental shelf within the Atlantic Region due to potential negative impacts on the sanctuary. The GRNMS Advisory Council has also worked to develop marine conservation recommendations and needs for the South Atlantic Bight in response to the America the Beautiful initiative, which aims to protect 30% of U.S. lands and waters by 2030. GRNMS also coordinates with law enforcement agencies to optimize patrols of the sanctuary based on known vessel use patterns to ensure compliance with protective regulations.

Conclusion

The sanctuary’s offshore location limits direct human pressures on water quality, habitat, and living resources, and most data suggest that observed changes in the sanctuary have been largely driven by natural factors, resulting in status ratings of good to good/fair for GRNMS resources. However, temperature, CO2 levels, and storm frequency increased, and some focal species for GRNMS, such as North Atlantic right whales, faced ongoing problems. A number of data gaps precluded a full assessment of trends in some aspects of water quality, contaminants, and the status and trends of some focal species. Ecosystem services were in good/fair to fair condition. Particular challenges included a lack of staff capacity to provide sanctuary education and outreach opportunities during the study period and a lack of awareness of the sanctuary among the general public. However, increasing awareness and the recent dedication of the Gray’s Reef Ocean Discovery Center resulted in an improving trend for both education and sense of place. This condition report will support the development of a new management plan, and its findings will serve as an important foundation to help GRNMS set future priorities based on identified needs and ensure current management and regulatory responses are adequate. GRNMS staff will be fully evaluating the data gaps and information needs highlighted in this report to ensure the next management plan addresses the highest priority topics and management actions.